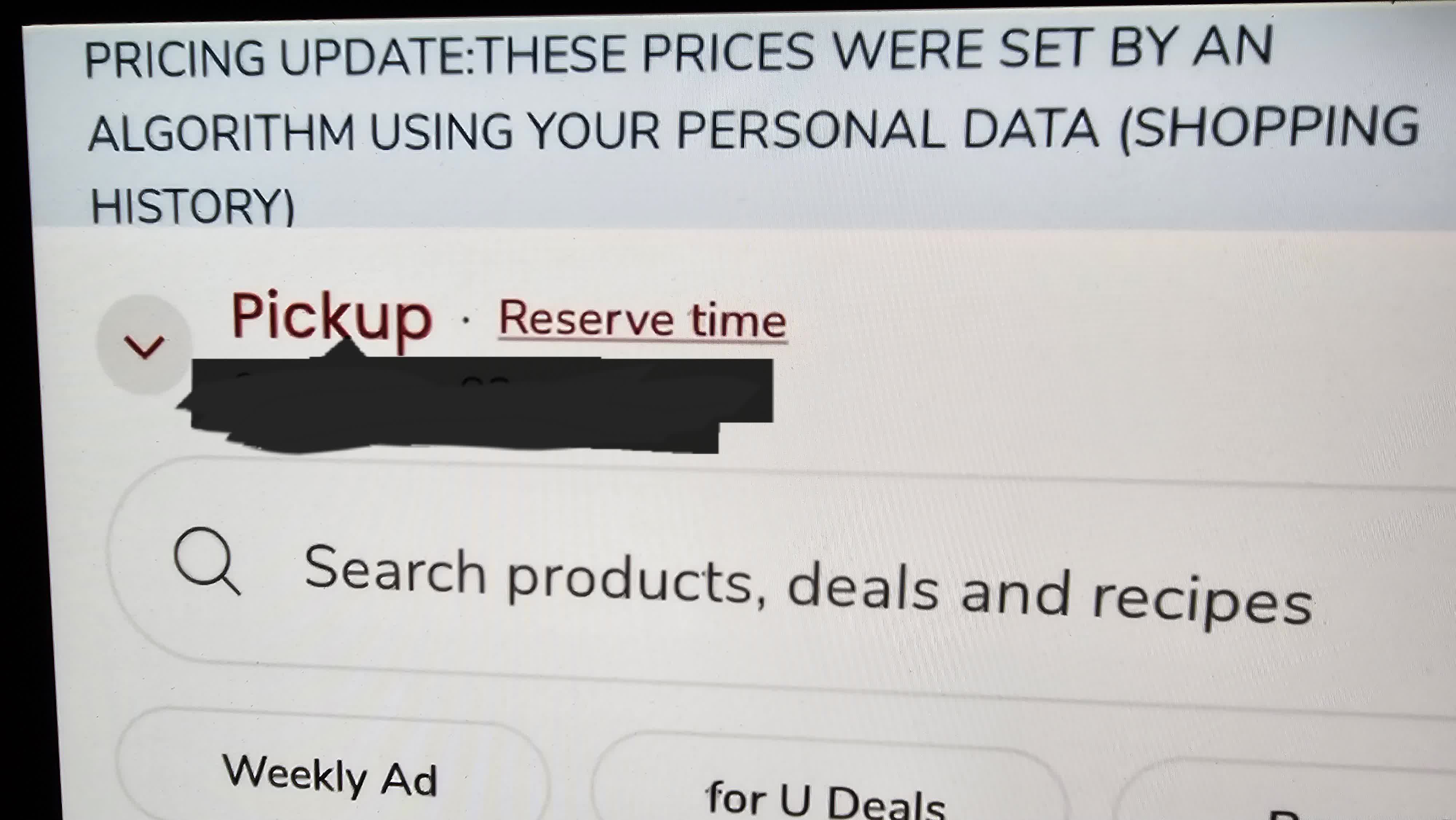

Winners & losers: As Black Friday deals flashed across screens in New York this year, some shoppers saw something new beneath the price tag: a short, blunt line of text. "This price was set by an algorithm using your personal data." That sentence is not a suggestion or a best practice. It is now required under a new law.

New York is the first state in the US to require online retailers that use personalized pricing to display a disclosure. The regulation is part of a broader state budget measure targeting what regulators and consumer advocates call "surveillance pricing" or "algorithmic pricing" – adjusting prices for individual customers based on personal data, browsing history, device type, location, and other behavioral signals. The law does not ban the practice outright. Instead it forces transparency.

Personalized pricing is not new, but the tools behind it have grown far more powerful. In the early 2010s, travel site Orbitz made headlines when reporters exposed that it steered Mac users toward more expensive hotels than PC users, based on the assumption that Apple owners had more disposable income. That approach now looks crude compared to what many companies can do today.

Modern pricing algorithms can ingest a wide range of data: past purchases, how long a user lingers on a product page, whether they are browsing on a mobile device or desktop, their location, income proxies, and even behavioral signals such as mouse movements and scrolling patterns. Some systems use machine learning models trained on millions of transactions to predict how much a given customer is willing to pay, then adjust prices in real time.

Legal experts say the rule could become a model for other states. At least ten states have introduced bills that would either ban personalized pricing or require similar disclosures. California, where much of the underlying AI and data infrastructure is built, is considering its own restrictions. In Washington, federal lawmakers have proposed broad bans on algorithmic price discrimination, though none have passed yet.

The law has drawn strong reactions from both sides. Business groups, including the National Retail Federation, have challenged it in federal court, arguing that the disclosure is overly broad, misleading, and violates the First Amendment. In a lawsuit filed before the law took effect, the NRF claimed that the required notice is "ominous" and that it fails to distinguish between practices that benefit consumers – like targeted discounts – and those that harm them.

A federal judge in Manhattan, Jed S. Rakoff, rejected the group's request to block enforcement. He allowed the law to move forward, leaving the broader constitutional questions for later resolution. That decision has kept the disclosure requirement in place, at least for now.

Retail industry veterans say that large chains already use personalized pricing in limited ways, primarily through loyalty programs and targeted coupons. Chad Yoes, a former Walmart pricing executive and co-founder of retail consulting firm Waypoint Retail, told The New York Times that most major retailers are not systematically jacking up prices for individual shoppers across their main sites. Instead, they use data to offer discounts and promotions to specific customer segments.

Still, he warned that the New York law could undermine trust between retailers and customers. If every personalized offer comes with a warning that an algorithm set the price based on their personal data, shoppers may become wary of loyalty programs and targeted deals, even those that save them money.

Consumer advocates argue that the law does not go far enough. Groups like Consumer Watchdog, a Los Angeles nonprofit focused on consumer protection, had pushed for an outright ban on personalized pricing, not just a disclosure. They point to real-world examples where prices appear to vary based on who is shopping.

Justin Kloczko, a researcher at Consumer Watchdog, described a case from his own experience: when he and his wife requested rides from Chicago's suburbs to O'Hare International Airport at the same time, Uber and Lyft quoted him significantly higher prices than they offered her. The companies did not explain why, but the difference suggested that the apps were using personal data – such as past ride history, payment method, or device type – to adjust fares.

Uber has acknowledged that it is now displaying the New York disclosure to shoppers in the state, as required by law. In a statement, an Uber spokesperson said the company considers only geographic factors and real-time demand when setting prices. Lyft did not respond to a request for comment.

Legal and antitrust experts see the New York law as part of a larger shift in how governments are approaching AI and data-driven business practices. Goli Mahdavi, an AI and data privacy lawyer at Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner, said that algorithmic pricing bills are likely to become the next major battleground in AI regulation, after issues like deepfakes and automated content moderation.

Image credit: Consumer Watchdog